A study published in Geophysical Research Letters reveals that glaciers in western Canada, the United States, and Switzerland lost around 12 percent of their ice between 2021 and 2024. A 2021 study in Nature showed that glacial melt doubled between 2010 and 2019 compared with the first decade of the 21st century. This new paper builds on that research, says lead author Brian Menounos, and shows that in the years since, glacial melt continued at an alarming pace.

“Over the last four years, glaciers lost twice as much ice compared to the previous decade,” says Menounos, a professor at the University of Northern British Columbia and a chief scientist at the Hakai Institute. “Glacial melt is just falling off a cliff.”

Warm, dry conditions were a major cause of loss across the study areas, as were impurities from the environment that led to glacial darkening and accelerated melt. In Switzerland, the main cause of darkening was dust blown north from the Sahara Desert; in North America, it was ash, or black carbon, from wildfires.

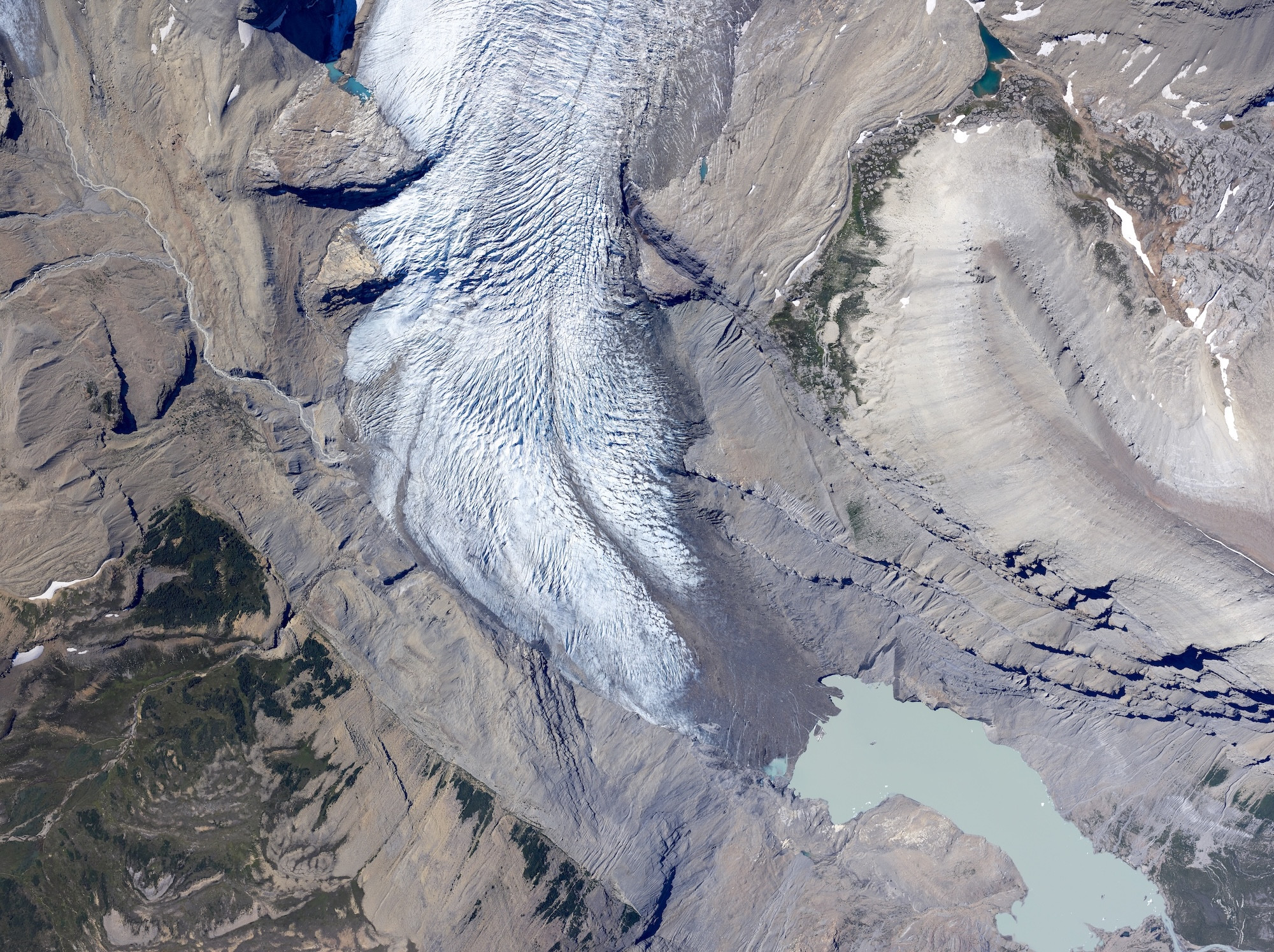

The research combined extensive aerial surveys with ground-based observations of three glaciers in western Canada, four glaciers in the US Pacific Northwest, and 20 glaciers in Switzerland, all of which are important for culture, tourism, and cool fresh water—and all of which are melting rapidly.

Snow and ice, when not obscured by dark particles, reflect the sun's energy in a process known as the albedo effect. To dig deeper into the North American story, Menounos and his collaborators used satellite imagery and reanalysis data to look at declines in albedo. They found that albedo dropped in 2021, 2023, and 2024, but the biggest declines occurred in 2023—the worst wildfire season in Canadian history.

“2023 was the year of record, no question,” Menounos says.

In contrast to reflective white snow, a glacier covered in black carbon will absorb more radiation from the sun. This heats up glaciers and accelerates melting. At Haig Glacier in Canada’s Rocky Mountains, glacial darkening was responsible for nearly 40 percent of the melting between 2022 and 2023, the researchers found. Yet despite such evidence, physical processes like the albedo effect aren’t currently incorporated into climate predictions for glacier loss, so these masses of ice could be melting faster than we realize.

“If we’re thinking, Well, we have 50 years before the glaciers are gone, it could actually be 30,” Menounos says. “So we really need better models going forward.”

In the areas covered by this study, the impact of glacier loss on sea level rise is small, but a longer-term decline in glacial runoff could impact human and aquatic ecosystems, especially in times of drought, Menounos adds.

In the shorter term, increased melting raises the risk of geohazards like outburst floods from newly formed glacier lakes. All of this poses questions around how communities should respond as well as plan for a future with less ice.

“Society needs to be asking what are the implications of ice loss going forward,” Menounos says. “We need to start preparing for a time when glaciers are gone from western Canada and the United States.”

Contact

Brian Menounos

Professor, University of Northern British Columbia

Chief Scientist, Hakai Institute Airborne Coastal Observatory

(250) 960-6266 (office); (250) 960-8923 (cell)

brian.menounos@unbc.ca

Media Kit

Download the media kit that includes this press release, the newly published paper, and photos with captions.

About the Paper

“Glaciers in Western Canada‐conterminous US and Switzerland experience unprecedented mass loss over the last four years (2021–2024)” was published in Geophysical Research Letters in June 2025.

Menounos, B., Huss, M., Marshall, S., Ednie, M., Florentine, C., & Hartl, L. (2025). Glaciers in Western Canada‐conterminous US and Switzerland experience unprecedented mass loss over the last four years (2021–2024). Geophysical Research Letters, 52, e2025GL115235.

https://doi.org/10.1029/2025GL115235

About the Partners

University of Northern British Columbia

The University of Northern British Columbia (UNBC) is a dynamic, research-intensive university that is consistently ranked among Canada’s best small universities. Offering excellent undergraduate and graduate learning experiences and research opportunities, UNBC conducts research that advances knowledge and contributes to the economic, social, and environmental well-being of the communities it serves. UNBC’s Department of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences is an innovative hub for exploring the complex interactions between people and the planet through integrative, experiential, and research-driven learning. Learn more at www.unbc.ca.

Hakai Institute

The Hakai Institute, part of the Tula Foundation, is a British Columbia–based scientific institution dedicated to advancing science on the coastal margin. Hakai pursues its mission from ice fields to oceans, leveraging its ecological observatories and other strategic locations on the province’s coast. The Hakai Institute partners with universities, NGOs, First Nations, government agencies, businesses, and local communities to move the needle on advancing long-term coastal research. Learn more at www.hakai.org.

Tula Foundation

The Tula Foundation is a British Columbia–based organization that harnesses science and technology to tackle urgent global issues. Tula takes a comprehensive approach to these challenges, from coastal biodiversity and public health to data management and mobilization. Along with rural healthcare in Guatemala, Tula’s work drives pivotal action for coastal conservation and ocean research in British Columbia and beyond. Learn more at www.tula.org.