May 2nd, 2025

Short Takes

Sunflower sea stars (Pycnopodia helianthoides) are clinging to life in the cold-water fjords of British Columbia’s Central Coast.

A new study suggests that cold-water fjords on British Columbia’s Central Coast could be marine refuges for sunflower sea stars (Pycnopodia helianthoides). The sea stars were once a common fixture of the Pacific Northwest intertidal zone. However, since 2013, sea star wasting disease (SSWD) has wiped out over 90 percent of the global sunflower sea star population between Alaska and Mexico. SSWD outbreaks have been linked to marine heatwaves, which are becoming more frequent due to climate change. This study indicates that consistently cold water could offer a potential refuge for the threatened sunflower sea stars.

Research collaborators at the Central Coast Indigenous Resource Alliance and member First Nations reported sightings of large sunflower sea stars in Central Coast fjords—a sign that remnant populations might have avoided SSWD. So Hakai Institute researcher Alyssa Gehman traveled to Burke Channel for a dive and saw a window into the past before SSWD took hold.

Compared with the sunflower sea stars found around offshore islands, the ones in the cold-water fjords were larger and more abundant, suggesting these areas act as refuges. Fjords have complex dynamics, and researchers observed that the sea stars were found below a surface layer of freshwater from snowmelt. This suggests that low-salinity surface water is a factor in the sea star’s habitat selection, emphasizing the way environmental systems interact to support species survival.

Sounding the Alarm for Global Glaciers

The Klinaklini Glacier—the largest glacier in North America, located in the Heiltsuk Ice Field—loses about one gigaton of water every year. Photo courtesy of Brian Menounos

As the world’s glaciers retreat, the magnitude of their loss becomes clearer—and more alarming. Brian Menounos, a researcher at the University of Northern British Columbia and chief scientist at the Hakai Institute’s Airborne Coastal Observatory (ACO), is part of an international research team that recently published findings on global glacial loss in Nature. Studying 19 different regions across the globe, the team found that between 2000 and 2023 these areas lost significant amounts of glacial ice. The greatest percentage of loss was in central Europe, which lost 39 percent of its glacial mass. Alaska lost nearly nine percent, and the southern Canadian Arctic lost over seven percent.

Canada is home to an astonishing 25 percent of Earth’s glaciers, and the Hakai Institute’s ACO collects important airborne data on western Canadian glaciers that’s helping link space campaigns—such as NASA’s Ice, Cloud, and Elevation Satellite—with high-caliber aircraft observations. This data will be crucial for improving regional and global forecasts of glacier loss, and for validating how we can measure glacier health from space.

In March 2025, Menounos was invited to attend the World Day for Glaciers in Paris—part of the 2025 International Year of Glaciers’ Preservation initiative—where he shared some results from his work with the ACO.

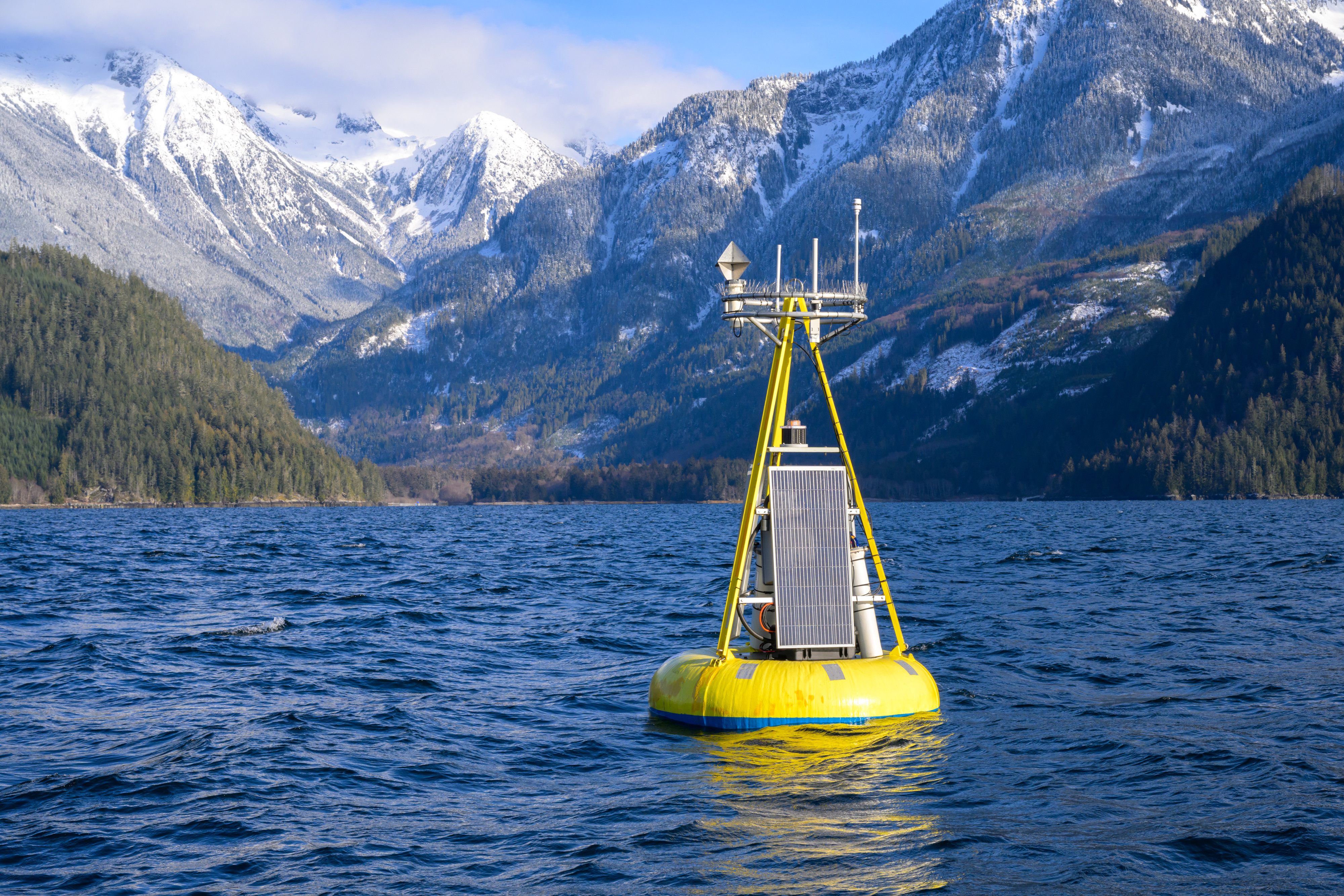

Bobbing for Data

Hakai Institute researchers deployed a newly refurbished buoy, equipped with a range of oceanographic tools, into the waters of Bute Inlet in February 2025.

Inlets play an important role as potential refugia for marine life amid a growing number of marine stressors, such as ocean acidification, but their constantly changing conditions can be difficult to monitor. Real-time observation platforms are a critical monitoring tool, yet there are few such platforms in British Columbia to track pattens of ocean acidification and carbon dioxide exchange.

The launch of a newly refurbished oceanographic buoy in Bute Inlet on the Central Coast will help contribute to our understanding of changing conditions within one of British Columbia’s refuge inlets. Deployed in early February 2025 by Hakai Institute researchers, the buoy is equipped to take high-resolution measurements of the surface ocean and lower atmosphere, including wind, temperature, salinity, oxygen, and carbon dioxide levels.

Bute Inlet is an area of particular importance to Homalco First Nation, which can now make timely decisions about the release of juvenile salmon from their hatchery, based on indicators such as phytoplankton abundance and algal blooms. Continuous data from the buoy will also support marine safety efforts and be available online for broader access.

In addition, data from the buoy will be integrated with Bute Inlet survey data dating back to late 2017, along with datasets from partners at Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the University of British Columbia. Maintaining these time series is crucial, since ocean science is facing increasing threats that put vital data records at risk.

Species of the Day

Hakai scientists and technicians use a careful photo-taking process—good lighting, flashes, and a black background—to document bioblitz organisms in the lab, like this Amphicteis mucronata tube worm.

Beauty, as the saying goes, is in the eye of the beholder. This Amphicteis mucronata tube worm might not be everyone’s choice for a charismatic organism, but this photo shows off its vibrant coloring and unusual form, which some will surely find beautiful

Submitted by polychaete expert Leslie Harris, the tube worm was a “Species of the Day” winner at the 2024 Quadra Island Bioblitz, where the Hakai Institute team gathered dozens of researchers for a three-week-long survey of the biodiversity of Quadra Island, British Columbia. You can learn more about the bioblitz and view the full list of winners here.